Duty Station:

Email:

Tel:

The spread of COVID-19 affected human lives globally; nationwide lockdown enforced a halt in travels to slow down the transmission. Similar to all other aspects of life, research activities were also held back as the crisis interrupted in-person data collection. In April 2020, the Food Security and Nutrition (FSN) Network hosted a virtual webinar attended by nearly 510 participants representing NGOs, donors, civil societies, academicians, and research entities from different parts of the world. More than 200 participants experienced challenges accessing on-site data collection/monitoring as part of their monitoring and research activities during the pandemic. As time goes on, each day brings new challenges in this pandemic, life adapts to a ‘new normal’, and we have learned to be agile and adjust our research methods to these changed conditions.

SHOUHARDO III program implementing in the eight remote char and deep haor districts transcends through a similar global scenario. The ongoing research initiatives called for innovative modalities that would allow the Program to obtain high-quality data without physical movement. I had the opportunity to conduct remote data collection (through individual voice calls, conference calls, zoom webinars, etc.) for four pilot assessments and six studies from April 2020 to June 2021. This shift from “face-to-face data collection” to “phone call data collection” came up with a whole new set of learnings and experiences since they comprise regions that lack sound cellular network coverage.

The pilot assessment process was crucial since the findings would confirm the viability and scalability of the study models and postulate future programmatic decisions. In the beginning, it was not easy pinpointing the accurate literature on remote data collection. Even if there were plenty of resources on remote modalities, none explained the economic, social, and cultural contexts that might work effectively for these rural communities of Bangladesh. As a result, we started from scratch rather than looking into the readily available knowledge. We kept on learning from each data collection and making the next one more systematized with fewer drawbacks. Here are few takeaways for researchers who plan to conduct phone surveys:

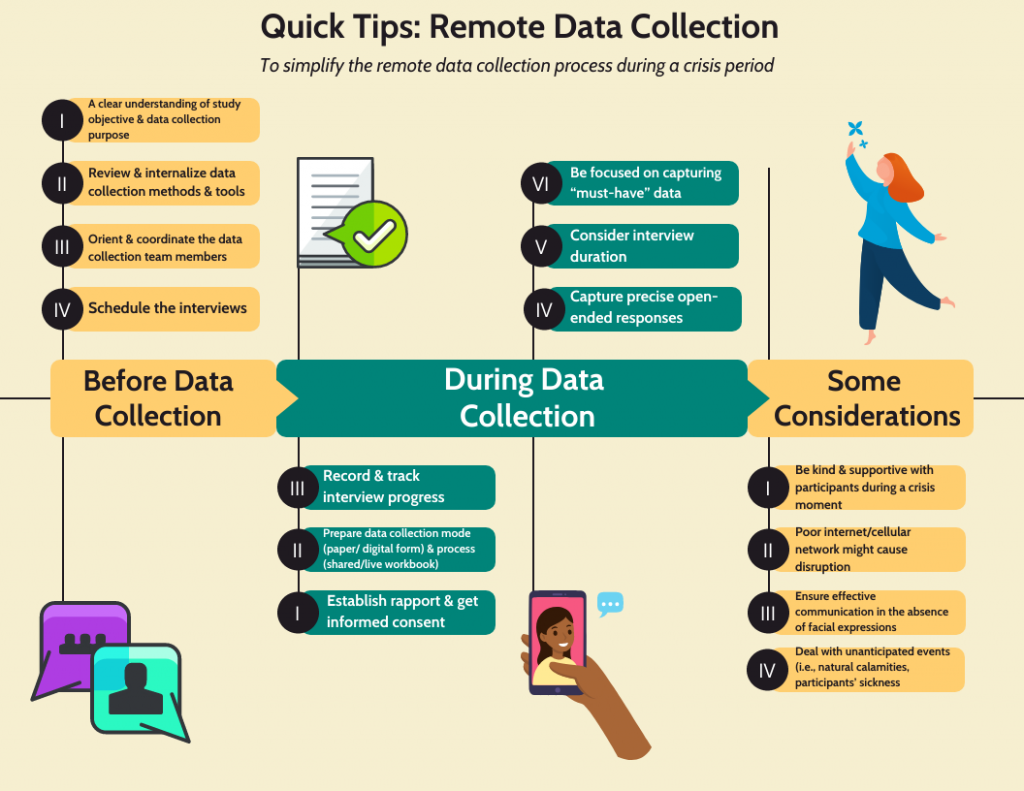

Make a thorough preparation: This is the first and most crucial phase, and transition can be intense if your team is accustomed to physical movement and face-to-face communication. Few things to keep in mind when it comes to planning –

- preparing and revising the data collection tools and data entry templates before initiating the remote data collection,

- organizing and orienting the data collection team,

- obtaining comprehensive information on data collection participants, and

- identifying the mode (i.e., voice calls, video calls, any software) of data collection.

A pre-call or a test-call for rapport building: Before conducting the actual interview, a pre-call could effectively develop an understanding between the interviewer and the interviewee. While respondents might be selected from various economic and social backgrounds, a pre-call can set the appropriate mode for remote interviews. It helped the respondents have mental and practical readiness (i.e., multiple members using the same phone in poor households, shared an alternative contact number, charged their mobile phones, or choosing a place to face fewer network issues for the interview).

Flexibility for the interviewees: I remember the first time we went for remote data collection in April 2020, rather than a single study, it was three pilot assessments altogether. The data collection team was inclined to have flexible scheduling and patience as the participants were from heterogeneous income groups, occupations, cultural practices, and, most importantly, dealing with this pandemic. It was the middle of Ramadan, my colleagues and I even agreed to conduct the interviews at odd times (just before or after breaking the fast or during dinner time); we had to remain flexible since the participants found that time convenient.

Expect the unexpected: Based on my comprehensive understanding of remote data collection, this was the most pivotal learning. There will be situations and questions beyond your planning and preparation. Once, we had to discontinue a virtual focus group discussion (taking place through Zoom) as a sudden storm hit the participant’s location. Similarly, we even had to call the same participant more than five times since they used the featured phones and kept disconnecting due to poor network.

Before one jumps to concluding which modality works best, let me share two different stories:

It was November 2020, my first in-person collection attempt after the lockdown and the COVID crisis. I interviewed a Local Service Providers (LSP) from Jamalpur district who shared her feelings and perception of working as a Sanchay Sathi[1] for one year and received her first-ever service charges (from running the savings group). I noticed how uncomfortable she was to open up about the received remuneration as she was anxious that her savings group members might hear. Even if she emphasized that she was ‘happy’ with the reduced payment, she could not help the dissatisfaction in her eyes. At that moment, I realized that she could have spoken more comfortably if it was a home-based private telephone interview. When “an outsider” visits the rural communities, it is not always simple to limit the presence of a curious neighborhood.

The next one took place in March 2021; we were in a focus group discussion with ten people sharing their experiences on arsenic testing by the Program-trained water quality testers. In that discussion, Abdul Majid, a SHOUHARDO III participant, shared how the testing identified arsenic contamination in his tube well. I looked at him closely, his eyeballs turned reddish from drinking arsenic-contaminated water for more than a year. If we opted for remote data collection, we would have missed that valuable observation in the findings.

Taking the above experiences into account, both from face-to-face data collection activity, they taught me an important lesson: we must choose the method that will best serve our purpose in that situation. While we cannot predict the future, we have to capture good practices and learnings from ours and others’ experiences. Later, the Program obtained data within a precise timeline by blending remote and in-person data collection modalities, as crisis often sparks innovation!

[1] Sanchay Sathi is a type of Local Service Provider trained and developed under the Village Agent (VA) model. The savings peer helps the community forming and facilitating their own Village Savings Loan Association (VSLA) at a predetermined service fee.